The Story Painter

Tight schedules and professional distance have no place in David Sutherland's documentary films, where truth takes its time and the people are real.

January 08, 2006, By DAVID ZURAWIK | DAVID ZURAWIK,BALTIMORE SUN TELEVISION CRITIC

NO ONE MAKES documentaries the way David Sutherland does. And perhaps no one ever will; the toll is too great. Though not a household name like Ken Burns, Sutherland is considered by those who know documentaries to be one of the nation's greatest practitioners of the form. He also is renowned for his obsessive attention to detail, extraordinary use of live sound and his habit of living months, even years, with his subjects.

Before cameras rolled on his best-known work, PBS' The Farmer's Wife, a portrait of a young husband and wife as they struggle to save their farm, Sutherland visited 43 rural families and lived with each for as long as two weeks in search of the right couple. He then spent five additional years following Darrel and Juanita Buschkoetter and their three children to film, tape and ultimately chronicle their hardscrabble lives in Nebraska. The final product was seen in 1998 by 18 million viewers, an audience for a documentary exceeded on public television only by Burns' The Civil War, Baseball and Jazz.

Tomorrow night, Sutherland's newest project arrives: Country Boys, another anthropological masterpiece that intimately examines the lives of two high school students coming of age in Appalachia. The 60-year-old Massachusetts filmmaker spent seven years in and out of the hills of eastern Kentucky to complete his story. "The way I do it takes so long because I want you to get into their skin," he explains.

The documentarian's methods more closely resemble an ethnographer's than a television director's; he steeps himself in the minute details, emotions and struggles of their lives, trying to see the world through their eyes. "It's a dinosaur way to make films, because it's not cost effective," Sutherland says. "And I never tell kids to do it my way, which is third person and extremely close up. But I'm also cutting edge, because there was more audio in The Farmer's Wife than there was in Apocalypse Now -- and on Country Boys, there's even more audio yet. You have to be out of your mind to spend six months just mixing all the different audio tracks, but that's the way I do it."

Sutherland at times sounds more like a painter than a filmmaker as he talks about allowing viewers to feel as if they are part of the lives being framed on the TV screen. If film is his canvas, he primes it with research, carefully blocks out his story with narrative, then brushes in highlights and shadow with sound. Never mind closing the distance between viewer and object viewed, this filmmaker all but obliterates that distinction through his own intense identification and empathy with the people he films.

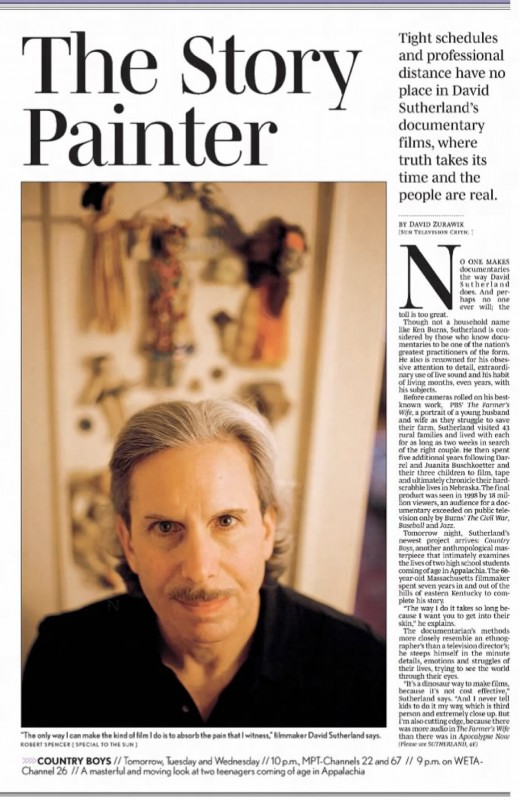

"The only way I can make the kind of film I do is to absorb the pain that I witness," Sutherland says. "I have to care about the people in the film so much because I'm a portraitist. I'm not an investigative reporter. To make my portraits, I need those emotional nuances. I need that -- I don't even know what the word is -- 'connection' to be able to feel and hear them sighing and breathing from 100 yards away. Getting that close leaves me battered emotionally and physically, but it is the only way of doing documentaries that interests me."

In these days of "ripped from the headlines" television, Sutherland's commitment to capturing the nuances of everyday lives is nearly unheard of, says Michael Sullivan, executive producer for Frontline, the Peabody-Award-winning series responsible for bringing The Farmer's Wife and Country Boys to PBS. "David has been making films for almost 30 years, methodically perfecting his singular vision of cinematic portraiture, trying always to get the viewer as close as he possibly can to the actual reality of his characters' lives. I often tell David when he's groaning in the cutting room through one more day, that his method is the hardest kind of filmmaking there is."

The result, Sullivan adds, are "films that people understand, with stories they care about -- films that illuminate and touch all of our lives,"

A few detours

Little about Sutherland's early career suggested that he would become one of the most revered documentarians of his time. A dyslexic whose disability was not diagnosed until he was 20, Sutherland graduated with a B.A. from Tufts University in 1967. While he spent 1969-70 as a film student at the University of Southern California, he left before earning an M.F.A and did not go into making documentaries full time until more than a decade passed.

Beyond stints on a kibbutz in Israel and an oil rig off the coast of Louisiana, he spent much of the next 14 years in the tire business -- first selling them in Colorado and Montana for his uncle and then returning to his hometown of Boston to take over his father's tire and appliance store in East Cambridge.

The answer he offers in Country Boys is complicated. While the film depicts Johnson's rundown family trailer sitting on what seems a garbage dump, it also includes the well-kept, brick home of McGuire, the grandmother who cares for Perkins. And though the trailer, set on a dirt road in what Johnson calls a "holler," appears isolated, it houses a computer that links the teenager to MTV, CNN and the outside world. Johnson himself seems bilingual -- speaking to his father in an Appalachian dialect and at school in much more formal English, learned from watching soap operas.

The visual imagery is multi-layered as well. For every strip-mine-scarred hill, there are shots of breathtakingly beautiful mountains, trees and fields. There are no easy answers or stereotypes in a Sutherland film -- at least, that's the way David Greene, the director of the David School, sees it. Green initially turned Sutherland down when the filmmaker asked to roam the school with his cameras, putting body microphones on teachers and students alike. "I had seen where many cameras had come through Appalachia with an agenda, and I felt that over the years, the media in general seemed to be reinforcing stereotypes rather than offering a balanced view," he said at a PBS press conference in Los Angeles after a screening of the film. "And so, not being really acquainted with documentary work, I was very protective. I said, 'No.' I couldn't imagine cameras in the school. I could not imagine being miked."

But at Sutherland's urging, he watched The Farmer's Wife. "I was so touched and moved by it," the school director said, that he granted unfettered access. "And I have to say David and the crew were very respectful to let life be as it is," says. "There were days I'd walk into work and I had no idea who was on a wireless mike, which is sometimes scary. But I found it very comfortable, you know, once you kind of get used to it. And they showed a great deal of respect for the boys, their lives, the region, and I'm really very pleased with that.

The best testimony as to Sutherland's success may come from the young men themselves. "It's real honest and true," Perkins said in a telephone interview last week. "Overall, I have a good feeling about it. You know, it's hard to sum up three years of peoples' lives in six hours of films, but it has the basics of me and Chris down right." Johnson, too, praised the film for its verisimilitude: "I believe the movie was truthful to the point that that's how I wanted it to be," he said at the PBS press conference. "I mean, I didn't want to see anything buttered up and so forth. I just wanted the truth. I mean, we've each lived interesting lives, some good, some bad. But, at least, they're all in their truest form."

Suffering for art

The film took 2 1 / 2 years longer and $500,000 more than budgeted. Health issues contributed to the slower pace of production: Sutherland worked throughout the filming of Country Boys with a torn rotator cuff so severe that one shoulder was noticeably higher than the other. Members of his crew routinely pushed it into place so that he could hold a camera.

The filmmaker had injured the shoulder while filming The Farmer's Wife by falling off the Darrel Buschkoetter's pickup truck. Buschkoetter was racing to deal with a cow that died in pasture, and Sutherland had jumped on the back of the truck to record sound. He also injured his pelvis in the accident, and it has yet to be realigned.

During the filming of Country Boys, he re-injured the shoulder and pelvis when hit by a Jeep while walking along the road. Now he is wrestling with the "post-partum depression" triggered by the end of a project --and from "absorbing all the pain" to which he bears witness with each film. When Frontline's Sullivan asked him at a press screening if he would do another film, Sutherland inexplicably burst into tears. "I say I'm 16 going on 60, and as a filmmaker, I feel like I've never been better. I know I've never been better in terms of being in control. But when I was asked about doing another film, I was just overwhelmed with the knowledge that I won't do anything that isn't meaningful to me. And I'm not sure what that will be," he says.

"David is not like other people," Sullivan says. "He has rare talents. He always tells me he thinks his brain is wired differently than other people. He's quite eccentric in his ways, but he's going for it. He goes for the heights -- he really does and he gives us filmmaking that's as close to real life as it is ever going to get. There's no barrier between the viewer and experience -- that's what he's after -- and I think he achieves it in this film."